[ 2 ]

The Anatomy of a Great Story

The Architect Analogy of Explaining UX

The first blog post I wrote and published was “An Information Architect vs. a Normal Architect.”1 It’s from 2010. In it, I explain what I do for a living by drawing parallels between planning out a house and planning out online experiences and strategies. Ever since I was a little girl back in southern Sweden, I’ve been fond of analogies and metaphors that can capture the imagination and make you see something, whether it’s actually there in front of you physically, or is just a mental image in your head.

Creating stories has always been my way of articulating and connecting things, from aspirations to drawing parallels between what’s going on in my life and the people and experiences I encounter. I hold a love for piecing things together, and I’ve often talked about how being a UX designer is a bit like being a spider. Not in the sense of a creature that kills its prey and eats it, but one that carefully spins its intricate web, makes everything come together, and has an overview of everything that is going on—how it’s all connected and how a change over on one end will affect everything else.

The spider analogy might not be that common. But the analogy between information architecture, or UX design, and building a house is, and I am in no way the first to come up with it. That said, it’s been the way I’ve responded to and later preempted the blank stare that usually comes when I tell people that I’m a UX designer. Though the house analogy often leads to some follow-up questions about what I actually spend my time doing, the one thing I love about UX design is that there are so many parallels we can draw to our day-to-day lives, and to other professions. We can easily adapt our explanations of UX design based on who we’re talking to. It’s also an incredibly fascinating field, as there are so many other disciplines that we can learn and draw from, such as writing books like my dad, being an architect, or a landscape architect like my brother Johan, or an actor like my partner D.

We all work with experiences in different ways, but each of us is a storyteller dealing with how the stories we’re working with will take shape and be acted out. Whether it’s my dad putting it down in words, my partner acting out the script he’s been given, my brother planning out a physical space, or me defining what the story means in the form of an online and offline experience, each of us works with character development, the actual narrative, and where it will all lead to. For my dad it’s about structuring a story from the first page to the last. For D, it’s about the first part of his performance—a line, a movement, or a gesture—to the last. For my brother, it’s about the physical experience and the role it will play in people’s lives, and for me it’s about where it all begins and the actions I want the user to (be able to) take throughout and at the end.

In each of our professions, we’re working with a promise of what’s to come. In one way or another we want to inspire the people on the other side, whether they are the readers of dad’s books, D’s audience, the people who will visit the spaces my brother designs, or the users who will use the product experiences I’ve worked on. My dad and I, in particular, are responsible for putting all the little pieces together and planning out, to lesser or greater detail, where the story begins and where it will end. At times we create simpler, more linear stories and journeys. Other times they jump back and forth between this, that, and the other. The process may seem chaotic or arbitrary, but it’s all choreographed, from the high-level picture it paints to the little details that make all the difference to the story as a whole.

It’s dad’s fascination with and passion for making all the pieces come together when he writes books and the similarities this has with the work of a UX designer that first sparked the idea for the talk that later became this book. Just as there are tried and tested principles, tools, and processes for delivering great work and projects in UX and product design, there’s more to writing a good story than just putting pen to paper. In this chapter, we’ll look at what makes a great story, including how to structure it, and the elements it should contain, starting with Aristotle’s seven golden rules of storytelling.

Aristotle’s Seven Golden Rules of Storytelling

Aristotle was the first to point out the interrelation between the way we tell stories and the raw human experience of the same. Back in 300 BC, he wrote a work called Poetics that examines the relationships between character, action, and speech, and the reactions a play evokes in the audience. Through his work, he concludes that these seven golden rules of great storytelling exist:

1. Plot

The arrangement of the incidents (actions) that take place

2. Character

The moral or ethical character of the play

3. Theme/thought/idea

The reasoning that explains the characters or story background

4. Diction/speech

The conversation between the characters but also the narrator

5. Song/chorus

The chorus and sound that supports the story

6. Decor

The design of the place in which the story takes place

7. Spectacle

Something that makes a real impact on the listener and that they’ll remember

Even though reading Aristotle’s Poetic won’t give you a Buzzfeed-style how-to guide to writing a great story, many interpretations of his work have made the seven golden rules easier to understand. Based on the industry they’re applied to, the seven golden rules have been given slightly different names. Table 2-1 gives two examples of how the names of the seven rules have been adapted to be more appropriate for the subject in question.

Table 2-1. Aristotle’s seven rules adapted to the film and UX industry (source: Jeroen Vaan Geel2,3)

|

ORIGINAL |

FILM INTERPRETATION |

UX INTERPRETATION |

|

1. Plot |

Plot |

Plot |

|

2. Character |

Character or stars |

Character |

|

3. Theme/thought/idea |

Idea |

Theme |

|

4. Speech |

Dialogue |

Diction |

|

5. Chorus |

Song/music |

Melody |

|

6. Decor |

Production design/art direction |

Decor |

|

7. Spectacle |

Special effects |

Spectacle |

While Aristotle’s principles were aimed at Greek theater, they remain relevant to this day and are even considered essential for writing good film screenplays. Though Aristotle considered plot to be the most important element, above character, most screenwriters today would argue that plot and character are two sides of the same coin.4

Throughout this book, we’ll come back to Aristotle’s seven golden rules of storytelling in reference to product and UX design. Before that, however, we’ll take a look at what else should be present in a good story.

The Three Parts to a Story

In addition to the seven golden rules of storytelling, Aristotle discusses the whole of a story and defines it as “that which has a beginning, a middle, and an end.” He further goes on to define a beginning, a middle, and an end as follows:

A beginning is that which does not itself follow anything by causal necessity, but after which something naturally is or comes to be...An end, on the contrary, is that which itself naturally follows some other thing, either by necessity, or as a rule, but has nothing following it...A middle is that which follows something as some other thing follows it.

His overall conclusion is that “a well-constructed plot, therefore, must neither begin nor end at haphazard, but conform to these principles,” meaning that the events should follow each other by probability and have a causal chain. Jean-Luc Godard, a French writer/director and one of the pioneers of the French Nouvelle Vague argues, “A film should have a beginning, a middle and an ending, but not necessarily in that order!”5 As we’ll cover later in this chapter and throughout the book, when it comes to storytelling for digital products that have to work across multiple devices and touch points, elements aren’t necessarily linear, but the three parts still hold true.

Though Aristotle never said that there should be three acts in a drama, the three parts—a beginning, a middle, and an end—have given rise to the three-act structure used in much of traditional storytelling.

The Art of Dramaturgy

The process of applying structure to a story is called dramaturgy. Merriam-Webster defines it as “the art or technique of dramatic composition and theatrical representation.” In its broader definition, dramaturgy deals with how to shape a story into a form that can be acted by giving the work a structure.

Dramaturgy was invented by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in the 18th century and is a practice-based as well as practice-led discipline that looks at the context of the play in a comprehensive way. This context can include anything from the environment (physical, social, economic, and political) in which the action takes place, to the psychological underpinnings of the characters, to how the play is written (structure, rhythm, flow, and choice of words).

The person who is the expert on this is called the dramaturg, or production dramaturg in the United States. This person is often involved throughout the many phases of a production, influencing casting and providing input on the in-progress state of the play in order to help shape the performance and story in the right direction by working with the director and the cast.

The overseeing role of the dramaturg is not too different from that of a lead. The responsibilities of a lead can vary between organizations. When I worked at the digital agency Dare, the experience leads to looked after a client account from a UX point of view, by ensuring consistency across projects and providing a clear understanding of user and business needs among all team members. Experience leads were also responsible for understanding the bigger picture, in terms of where a specific project would sit, so that all things related to the user experience and the business side were considered. Those of us who were experience leads were part of resourcing, most UX, design, and technical reviews, and worked closely with those respective leads to make sure everything came together.

In addition to the similarities between the role of a dramaturg and a lead, the art of dramaturgy is something that greatly benefits product design, as it’s focused on giving the work a structure. Two of the most famous works of dramatic theory are Aristotle’s three-act structure and Freytag’s pyramid.

Aristotle’s Three-Act Structure

Aristotle’s three-act structure consists of a beginning, where the plot is set up; a middle, where the plot reaches its climax; and an end, where the plot is resolved. To this day, the three-act structure is a model used in screenwriting, divide the narrative into three parts.

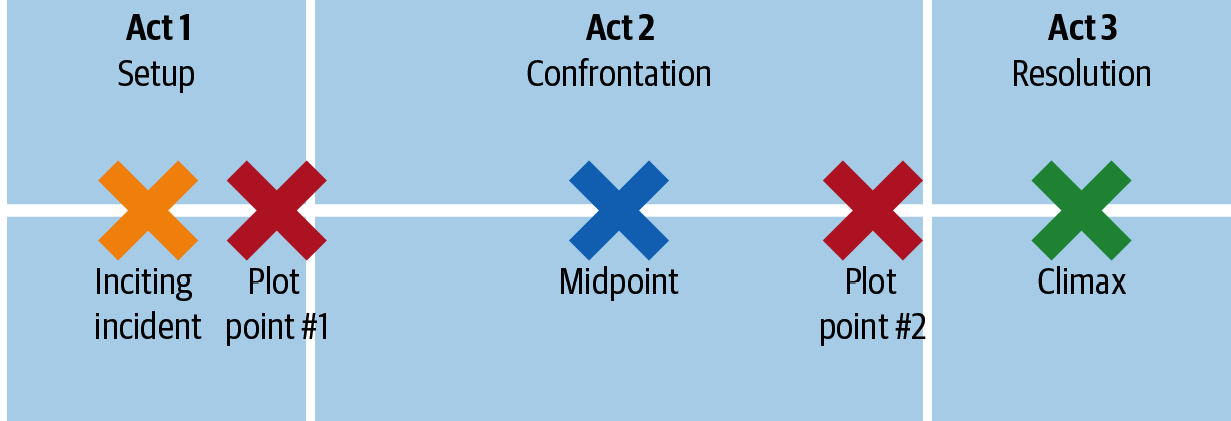

The parts, or acts, are connected by two plot points—key events that spin the story in a new direction. The first plot point occurs at the end of Act 1 and the second one at the end of Act 2, as seen in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1

The three-act structure

Act 1

The first act, the setup, is usually used for exposition. Act 1 the main characters, their relationships, and the world they live in are developed. A bit later in the first act, the inciting incident occurs: the main character, also known as the protagonist, is confronted with something to solve, leading to a more dramatic situation known as the turning point. The first plot point signals the end of the first act and is where the dramatic question is asked—for example, will they live happily ever after—ensuring that life will never be the same for the protagonist.

Act 2

In the second act, the confrontation, or rising action, the protagonist attempts to solve the problem initiated by the first turning point. In this act, the protagonist often lands in a worse situation than before due to not yet having the skills required, or not knowing how to deal with the antagonism with which they are confronted.

The second act is where the character development, or the character arc, takes place. The protagonist not only has to learn new skills, but also come to a higher awareness of who they are as a person and what they are capable of doing, which often in turn changes who they are. More often than not, this challenge requires the help of a mentor or co-protagonist.

Act 3

In the third act, the resolution, the main story and all the substories come together in the climax—the most intense scene or sequence, where the dramatic question is answered. Here, we find out whether the boy and the girl will live happily ever after, as well as where the protagonist and the other characters are often left with a new sense of self.6

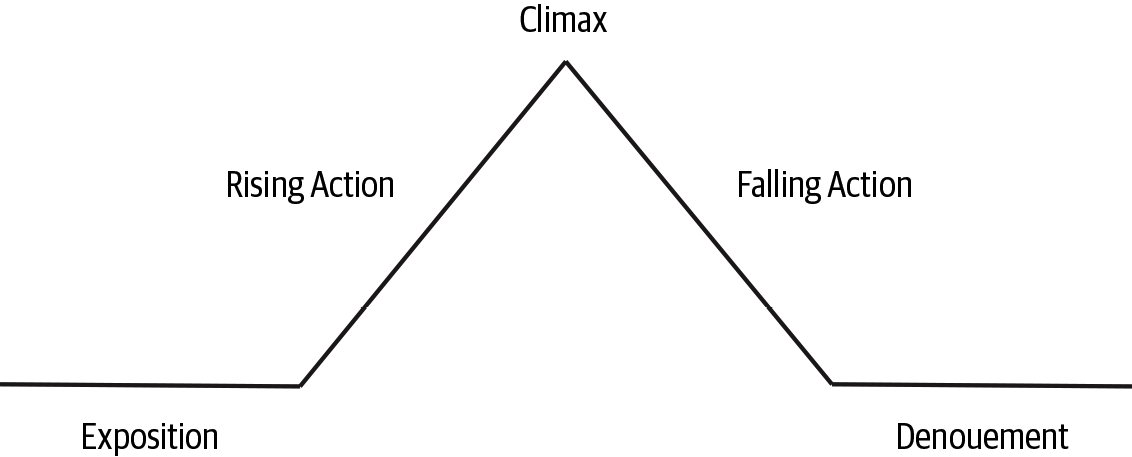

Freytag’s Pyramid and Criticism of the Three-Act Structure

There is some criticism of the traditional three-act structure, including that it’s too focused on plot points rather than character, and that it was made for theater. As an extension of that, the three acts are arbitrary and don’t, for example, fit with commercial breaks for TV series and films. As we’ll look at in Chapter 5, “Defining and Structuring Experiences with Dramaturgy,” there are also a number of interpretations and further work done on the acts and their plot points. One of the most important alternatives is the work of Gustav Freytag (Figure 2-2). In the late 19th century, he published The Technique of the Drama, which is considered the blueprint for the first Hollywood screenwriting manual. Contrary to Aristotle’s three acts, Freytag saw five parts to a story—the exposition, the rising action, the climax, the falling action, and the denouement (also known as the resolution).

Figure 2-2

Freytag’s pyramid

Exposition

This part of the story introduces important background information, including the setting, the characters’ backstories, and events that have taken place before the main plot. This information can be conveyed through background details, flashbacks, the narrator telling a backstory, or through dialogue or the characters’ thoughts.

Rising action

During the rising action, a series of events take place that build toward the point of greatest interest—the climax. These events begin immediately after the exposition and are often the most important part of the story because the entire plot depends on them.

Climax

The climax is the turning point in the story that changes the fate of the protagonist. Here the plot begins to unfold in favor of the protagonist or the antagonist, and the protagonist is often required to draw on hidden strengths.

Falling action

During the falling action, the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels, and the protagonist either wins or loses.

Denouement

Similarly to how the rising action builds up to the climax, in the denouement the final events take place, from the falling action to the ending scene. The conflict is resolved, and a sense of normality is created for the characters as the complexities of the plot are “untied.”

What Dramaturgy Teaches Us About Product Design

What both Aristotle’s three-act structure and Freytag’s pyramid teach us is that there are certain acts to a story: it begins, something happens, and then some, and then it ends. When it comes to product design, we’re often too focused on the details and forget that the overall narrative structure needs to be defined. As Aristotle pointed out, the way we tell a story has an impact on the raw human experience of the same. The way we structure the experiences of the products and services we work on will shape what the user on the other end thinks, feels, and does.

The Circular Nature of Digital Product Experiences

Although Aristotle’s seven principles for good storytelling, the three-act structure, and Freytag’s five acts, were meant for linear and finite stories, most of our experiences online are interlinked and have no universal beginning or end. In fact, when it comes to product design, applying storytelling principles is a matter of circular narratives: each circle links up with other circles, forming a chain of substories, some independent and some more closely linked. This applies both to the various parts of an experience as well as to the overall process in which each part—be it strategy, UX design, visual design, or development—overlaps and depends on the others as well as their own unique area of work.

As for how the parts of a product experience make up a chain of substories, just think of the journey a user might take in making a purchase. This type of end-to-end experience often consists of multiple smaller experience circles that are linked. It may start with the user spotting a product on social media, clicking the link, and ending up on the blog of the influencer whose post they’d seen the product in. As users warm more to the product, they enter a more active research phase: they visit the website where the product is sold, and potentially go off to look for the best price on other websites or see how it compares to competitor products, or both. The higher the price point, and depending on the type of product, the research (and eventually the consideration phase, where options are narrowed down), may be longer. This phase also may involve more touch points, including offline ones, such as speaking to friends and family and/or visiting a physical store before going back online again. The user might make a final check of the original blog post where they learned about the product for validation and then repeat their research one final time before deciding on buying the product. In essence, interdependencies and overlaps exist, and very few journeys happen in one go, but instead include breaks between the first and the final step.

Multiple Beginnings, Middles, and Ends

When I was a child, I at one point got this idea in my head that the world was flat and existed at the bottom of a milk carton. I think it stemmed from a kids’ album we used to listen to that described the world as being flat as a pancake. In my imagined view of how our flat-bottom-of-the-milk-carton world worked, the milk carton belonged to giants, and these giants would sometimes shake the carton, which, I figured, must be what made waves and earthquakes and the like.

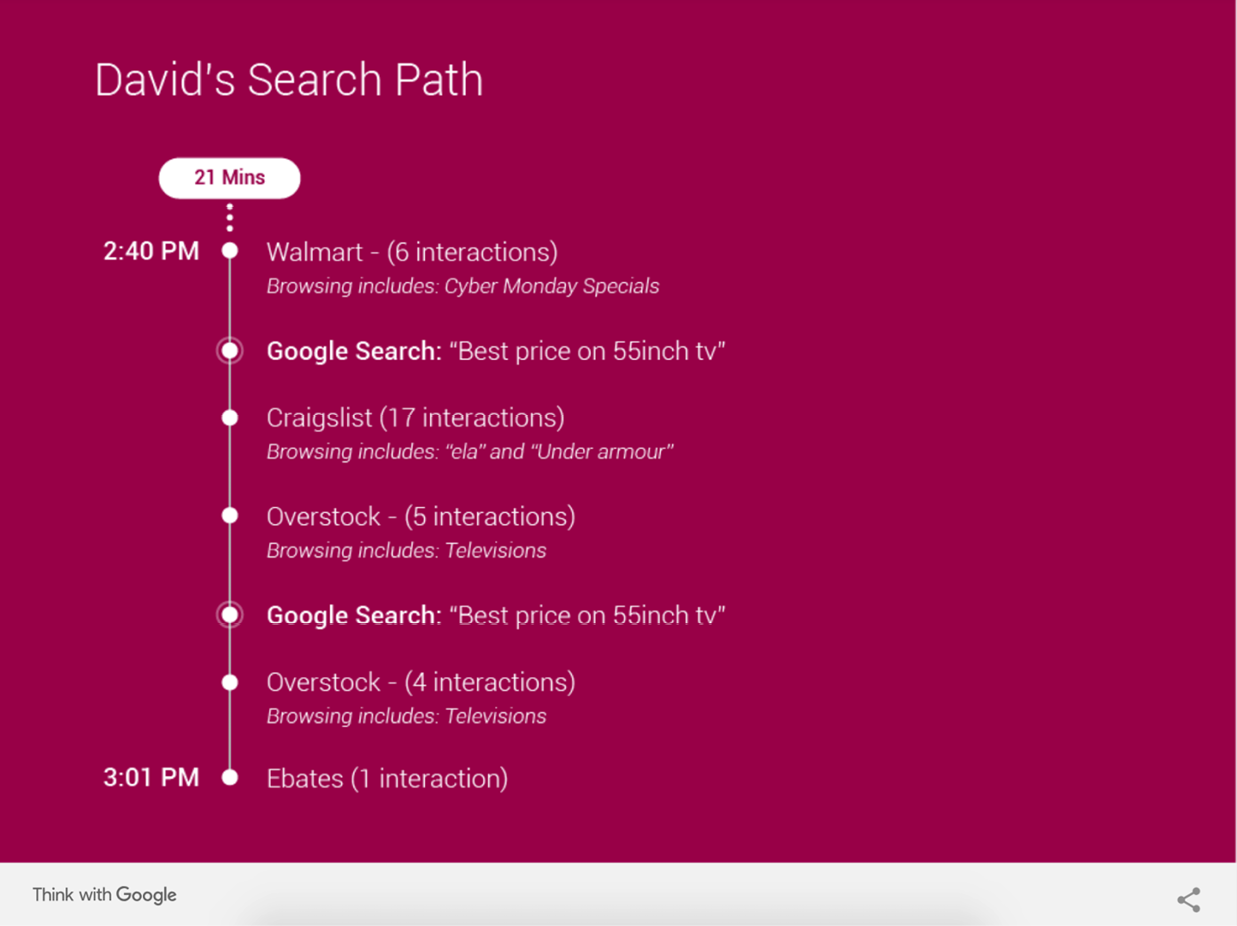

If we imagine that a giant shakes our milk carton filled with overlapping and intricately linked circles of stories, then as these circles shuffle around, some will suddenly overlap and connect with new or different substories. While I now know, for sure, that we don’t live at the bottom of a milk carton, and that giants shaking us around doesn’t cause natural disasters, our online experiences are constantly shaken and stirred, in a way that throws us off our path and onto a new one, where a new substory begins. At times we choose whether we continue our journey on a different site or through a chat with friends (Figure 2-3). Other times these shifts are more haphazard—caused by things we spot while casually browsing, or by notifications that pop up, or by things that we see that our friends and acquaintances or peers have also seen.

Figure 2-3

An example of the complexity of users’ online paths to purchase with multiple interactions on different websites7

Narrating the Chaos

The chaos of the user’s journey—as well as our lack of control over how users arrive and experience our products and services, and on what medium—is what makes the role of storytelling so important. Regardless of where the user’s journey starts and ends, and however interlinked or haphazard it is, the user is still going on a journey. Wherever they are in that journey and whatever page or view they are on, as UX designers, product owners, marketers, and startup founders, we need to make sure that we meet their needs right then and there, and on the next leg of their journey as well.

Even if the ending won’t ever be as finite as Aristotle defined it, but instead will spark the next part of the story, we should still aim to make the user’s journey more structured. Though the experience will differ among users, each user’s journey will still have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Adapting to How the Journey Begins

There’s a nice parallel to the Arabic alphabet here. Arabic is written from right to left; each letter in the alphabet has a slightly different form, depending on whether the letter comes in the beginning, middle, or end of a word. Not all letters can join to the following letter (to the left), but all letters can join to the preceding one (to the right).8

Similarly, we won’t always be able to control how the journey ends for the products and services that we design, but we can always ensure that we do our best to join up with the start of a user’s journey. This is true no matter what and where that is. We can design for multiple entry points and plan out what the experiences should look like from the start to the end of what we can control. In Chapter 7, “Defining the Setting and Context of Your Product Story,” we’ll look at how the context impacts the user’s experience and what we as UX designers should consider and adjust according to that context. Next we’ll look at what we can learn from other forms of storytelling.

Five Key Storytelling Lessons

The power of a good story lies in the emotional connection that it creates with its audience. Without this emotional connection, there really isn’t a story to speak of. But what else sets a great story apart from an average, or even good one? What is it that makes films like Toy Story, Monster’s Inc., and The Lion King box office hits and books like Harry Potter, the Twilight series, and the Millennium trilogy into best sellers?

When you search for the world’s best storytellers, a range of professions and people pop up. Some are historical people, leaders, or activists, as we’ve covered before. Others are storytellers in a more literal sense, like authors, playwrights, filmmakers, songwriters, and photographers. Every profession uses aspects of storytelling in slightly different ways, and we can learn something from all of them.

Traditional Storytelling and the Dramatic Question

The dramatic question focuses on the protagonist’s central conflict and is at the center of traditional storytelling. It’s the job of the writer to pose the dramatic question in such a way that the reader wants the answer to be a resounding “yes.” The writer must then create suspense by posing obstacles in the narrative that makes the reader want to read on, or keep on watching, or keep listening. It’s the dramatic question together with the suspense that makes the likes of Twilight into best sellers rather than your average novels. Even if the rest of the writing is mediocre, if the dramatic question is used effectively and the right kind of suspense is created, people will generally still read what’s been written.

A story often has more than one dramatic question, but the major, or central, dramatic question is the one that keeps us reading or watching. It concerns the protagonist’s main goal and, rather than being a reactive and internal one, it’s active and external. The question of whether the protagonist achieves this goal has to be answered with a yes or a no, and when it is, the story comes to an end. Similar to the red thread I mentioned in the previous chapter, the major dramatic question is the through line that we follow from the first act until the climax.

Here are some examples of dramatic questions:

- Will Romeo and Juliet ever be together? (Romeo and Juliet)

- Is Odysseus going to make it home from Troy? (The Odyssey)

- Will Scarlet win Ashley? (Gone With the Wind)

- Will Indy obtain the legendary Ark of the Covenant? (Raiders of the Lost Ark)

- Who/what is Rosebud? (Citizen Kane)

- Will Marlin find his son? (Finding Nemo)

In some cases, like in Schindler’s List, the major dramatic question isn’t 100% clear. Yet even in those circumstances, you still want to know what will happen next and how things are going to end. This desire to know how a story is going to end also applies when you are pretty sure from the start what the answer to the dramatic question will be, and that the boy and the girl will most likely live happily ever after.

Applying it to product design

Most products and services that we work on have both major and minor dramatic questions. Just think of the overarching goal of a user, buying a new TV, for example. As part of completing that goal, the user will have to carry out several smaller tasks, such as researching different brands, finding the best price, and locating a store that sells that particular TV or that can ship it to the user’s home. And then additional aspects might arise if the user needs help and turns to others for recommendations or even chats with the personnel in store.

By being clear on what the major and minor dramatic questions are, we help ensure that we keep the core of the product experience in focus. At the same time, we can remain aware of all the smaller aspects in the overall end-to-end experience.

Disney’s Magical Attention to Detail

Disney is often mentioned in conversations about great storytelling. The Walt Disney Company has created iconic films and the worlds, from the actual Disney theme parks to the vibrant worlds in movies like The Lion King, The Little Mermaid, and Beauty and the Beast. Everything in Disney’s creations, whether in the Walt Disney World experience or a film, is there for a reason. It’s one reason Walt Disney is hailed as a great storyteller. He had a fantastic ability to focus on the minute details and understand how all those nuances contributed to the big picture and the story that the audience experiences.

We often talk about this in design, and famous blogs like “Little big details” offer examples of lovingly created and thought-through details of an experience. These details are often referred to as delights, and although they are equally as often left out because of budget or time limitations, they can make a big difference to specific points in a journey for a user, and for the overarching experience as a whole.

Walt Disney’s attention to detail and desire to continuously make things even better—something he called plussing—transcends into the physical experience of the Disney theme parks. Walt Disney didn’t stop at just creating a theme park. Just as with his movies, he wanted to create a memorable experience that customers wouldn’t get anywhere else.

In 2008 work began on a major initiative that looked at every single aspect of the Disney World experience, from when visitors first enter the park to when they leave, with the aim of removing friction points. This work included looking at experiences like waiting in line for a ride, finding a place to eat, and then waiting to be seated in a restaurant. The solution was the Disney MagicBand.9

Together with the website and app that you as a visitor can use to explore the attractions, restaurants, and entertainment and make your itinerary and wish list, this wristband becomes the key to the magical kingdom. Through the use of RFID chips and triangulation technology, the wristband lets you skip queues, walk into a restaurant, and automatically have your food order placed and delivered to the table you’ve chosen. The system is based on preplanning; visitors reserve their rides and make restaurant and food choices in advance. But the end result is one that feels almost magical, down to the little things including that the staff knows your name as you walk through the door.

Applying it to product design

The drive to always do better and to pay attention to every single aspect of an experience is becoming increasingly critical for product design. As we’ll talk about in Chapter 3, “Storytelling for Product Design,” technological developments and user expectations are increasingly moving toward more tailored and personalized experiences that result in making users feel like the product or service knows them.

No matter what type of product or service we’re working on, we would do well to have Disney’s attention to detail combined with a deep understanding and care for how it all fits together. Everything is connected, and though our product may be only digital, the user’s overall end-to-end experience with it includes offline aspects, too. In Chapter 5, we’ll also touch on friction in product design.

Pixar’s Storytelling Lessons

Since releasing Toy Story in 1995, Pixar has developed a wealth of wisdom around storytelling, from a basic structure from which to start, to the simple advice of finishing your story, even if it isn’t perfect. Back in 2011, story artist Emma Coats tweeted 22 story basics guidelines that she’d learned from more senior people she was working with:10

- You admire a character for trying, more than for their successes.

- You gotta keep in mind what’s interesting to you as an audience, not what’s fun to do as a writer. They can be very different.

- Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about, til you’re at the end of it. Now rewrite.

- Once upon a time there was . Every day, . One day . Because of that, . Because of that, . Until finally .

- Simplify. Focus. Combine characters. Hop over detours. You’ll feel like you’re losing valuable stuff, but it sets you free.

- What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal?

- Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Seriously. Endings are hard; get yours working up front.

- Finish your story; let go even if it’s not perfect. In an ideal world you have both, but move on. Do better next time.

- When you’re stuck, make a list of what wouldn’t happen next. Lots of times the material to get you unstuck will show up.

- Pull apart the stories you like. What you like in them is a part of you; you’ve got to recognize it before you can use it.

- Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone.

- Discount the first thing that comes to mind. And the second, third, fourth, fifth—get the obvious out of the way. Surprise yourself.

- Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.

- Why must you tell this story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

- If you were your character, in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations.

- What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

- No work is ever wasted. If it’s not working, let go and move on—it’ll come back around to be useful later.

- You have to know yourself: the difference between doing your best and fussing. Story is testing, not refining.

- Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.

- Exercise: take the building blocks of a movie you dislike. How’d you rearrange them into what you do like?

- You gotta identify with your situation/characters, can’t just write “cool.” What would make you act that way?

- What’s the essence of your story? Most economical telling of it? If you know that, you can build out from there.

Applying it to product design

Some of these lessons provide practical references for exercises you can work through. Others provide guidance and food for thought, and others, yet again, like lesson 4, resemble what we already use in product design; in this case, user stories. These lessons teach us to get our ideas down on paper, focus on what’s most important, structure both the narrative and the way you work, and understand the importance of being able to identify with the characters of your story. All of which also applies to product design.

Video Games and Immersive Storytelling

Just as VR and AR place the user in the middle of an experience, what is so distinct in video games is that the player is part of an immersive world. As UX designer Joanna Ngai writes, “From start to finish, the player is dropped into a fully fleshed out world with a unique aesthetic that touches the interface, voice, and interactions the player has within the world.”11 Every aspect of this world has been designed, and the user is made into the main protagonist. The rules are what govern everything about the world, from what the user can and can’t do, to what touch points are available.

Applying it to product design

As the products and services we work on move from just being apps or websites that users interact with to experiences of intricately linked touch points, including but not limited to that app and/or website, every aspect of the experiences we work on will need to be fleshed out, too, just as in games. Users’ interactions no longer involve just clicks with a mouse, but often a mixture of clicks, touch, conversations with bots, gestures, and the use of their own voice, all aspects that we as designers need to define.

While users of the products and services we design have their own goals in mind, one of the defining characteristics of games is that the players have to learn what their goals are and how the world they’ve been immersed in works. Sometimes the goal is taught through the narrative of the game, as in The Legend of Zelda, the playable character Link is given the task of rescuing Princess Zelda and the kingdom of Hyrule from Ganon, the main antagonist, through dialog boxes. Other times it’s learn by play, or no dictated goal at all, as in Second Life.

Our interactions with technology increasingly involve touch interfaces, where the interactivity of certain elements isn’t always clear, as well as natural user interfaces (NUIs) and voice user interfaces (VUIs), where a user quickly has to go from novice to expert in order to be able to use them. As a result, we can draw a lot from the way games approach easy learning of goals and rules and the world in which users have been immersed—from making learning part of the experience rather than a separate tutorial, to providing feedback loops and visual cues.

Public Speaking and the Pull of Possibility in Storytelling

When you think about a great talk that you’ve seen and what it was that made it great, it’s often the motivated feeling that you were left with afterward. Johnson Kee, the founder and editor of 100 Naked Words, writes about the pull of possibility and quotes Tom Asacker’s The Business of Belief (CreateSpace Independent Publishing):12

We hunger for direction and inspiration. We want what’s important to us to get better — our bodies, work, home, and relationships. We want to imagine ourselves transforming our lives, and the lives of others. We want to feel good about our evolving narratives. It’s why we read books, scan the internet and flip through magazines. We’re looking for the before and after stories. We want to feel the pull of possibility; of moving beyond our existing reality .

Nancy Duarte, an American writer, speaker, and CEO talks about the pull of possibility and its importance in storytelling.13 Each and every one of us has the power to change the world, she says, and that it all starts with an idea. What separates one idea from another is the way it’s being communicated. If the idea resonates, she says, then it has the power to change the world, but it has to come out of us and be shared in order to do so—and the most effective way to achieve that resonance is through story.

When we hear a good story, Duarte says, our bodies react. We get chills down our spines, feel it in our stomachs, and get goosebumps. Our eyes dilate and our hearts beat faster. But when a presentation is given, she says, at times it flatlines.

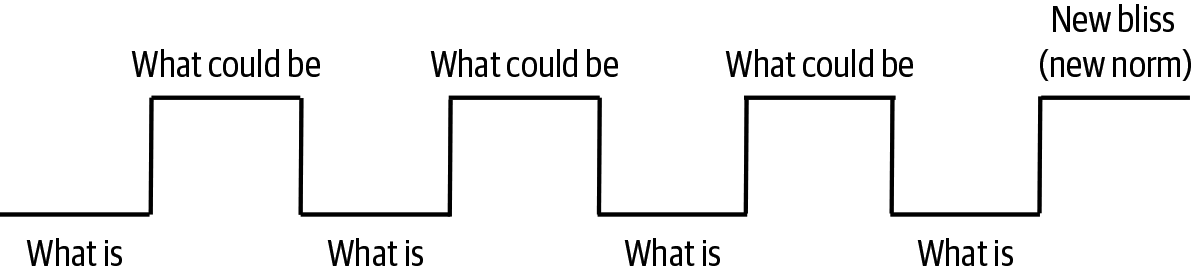

Duarte decided to look at other disciplines in order to see how they structure their stories. She researched Aristotle’s three-act structure and Freytag’s pyramid with its five acts and strong shape. This triangular shape sparked a question: what if great talks have a shape? By examining two of the most famous speeches of two men whose ideas have changed the world, Martin Luther King Jr. and Steve Jobs, she found that there was indeed a shape that could be overlaid on all great speeches. Just as in the three-act structure and any good or bad story, the shape she found in great talks has a beginning, a middle, and an end. It looks like in Figure 2-4.

Figure 2-4

The shape of great talks according to Nancy Duarte

The beginning of all great talks, according to Duarte, starts out with a flat status quo that rises to the loftiness of the future. This beginning is similar to the first plot point and the inciting incident in Aristotle’s three-act structure, where the dramatic question is asked. The gap between the status quo and the promise of the future needs to be big, she says, in order to plant the idea of the possibility in audience’s minds.

In the middle, the shape of a great talk shifts between what is and what could be, and this, she explains, is because you’ll encounter some resistance. People may love their world the way it is, and just as you have to move a boat back and forth in order to capture the wind and move forward so you pick up speed, you also need to move your presentation back and forth between status quo and the promise of what could be until you get to the end. The end includes the strong call to action, which she, just like Peter Guber, says that every good story or presentation should have.

Applying it to product design

When it comes to presenting our work, we’re often told that we shouldn’t tell, but show instead. While that often holds true, we need to plan out what it is that we’re going to tell, even if we mainly end up showing it. In Chapter 14, “Presenting and Sharing Your Story,” we’ll look at the role of storytelling and its importance when it comes to getting buy-in. We’ll also look at adapting the way we tell our stories, just as Steve Jobs did, to get the desired outcome no matter who the audience might be.

Summary

Although we might not be able to change the whole world, Duarte says that we all can change our own world by the way we tell our stories and include a strong call to action. What Aristotle and traditional storytelling teach us, in its simplest form, is that a good product design experience should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. As previously mentioned, at times we’re too quick to jump straight into the details, whether that’s a page or the requirements that we’re defining. By doing so, we lose out on taking a step back and actually defining and designing the overall story that our product should be telling, as well as how best to bring the small details to life.

What I hope to show you through the rest of this book is how you can help change the world of the people you design for by applying traditional storytelling principles and tools to the way you define, design, and sell in your product design projects. No matter what type of story you’re telling, you want to avoid that flatline and instead connect emotionally with your audience. And the way to do that is through truly shaping the story that you tell.

1 Read my first ever blog post over on https://oreil.ly/RzCgF.

2 From notes by Jalal Jonroy used while coaching graduates for their final thesis films at Film & Television: Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, https://oreil.ly/sHFiU.

3 Read the full Johnny Holland interpretation on https://oreil.ly/_nxiG.

4 “Character-Driven Vs. Plot Driven: Which is Best,” NY Book Editors (blog), https://oreil.ly/ZD5JU.

5 For more Jean-Luc Goddard quotes, see IMDb (https://oreil.ly/9u8xu).

6 “How to Write a Novel Using the Three Act Structure,” Reedsy (blog), June 15, 2018, https://oreil.ly/KOGoQ.

7 “How supershoppers use search to tackle the holiday season,” Think with Google, October 2016, https://oreil.ly/Ndxa_.

8 “Arabic alphabet table,” The Guardian, Febraury 6, 2010, https://oreil.ly/DcLuK.

9 Cliff Kuang, “Disney’s $1 Billion Bet on a Magical Wristband,” Wired, March 10, 2015, https://oreil.ly/_ThwX.

10 “Pixar Story Rules,” The Pixar Touch (blog), May 15, 2011, https://oreil.ly/jDea9.

11 Joanna Ngai, “What UX Designers Can Learn From Video Games,” Medium, September 22, 2016, https://oreil.ly/n-_E-.

12 Johnson Kee, “The Secret Structure of Steve Jobs’ Stories,” Medium, April 30, 2016, https://oreil.ly/hvip-.

13 Nancy Duarte, “The Secret Structure of Great Talks,” TEDxEast Video, November 2011, https://oreil.ly/qZGSV.